Why All This Paperwork?? 3 The Elixir of Death

Our story moves forward in time and across the Atlantic to the battlefields of the First World War. On the Eastern Front a young German Army medic tried to keep wounded soldiers alive in the filth of trench warfare. Try as he might, it was a losing battle. Even if he could sew the broken bodies back together, they would die from infection.

Our story moves forward in time and across the Atlantic to the battlefields of the First World War. On the Eastern Front a young German Army medic tried to keep wounded soldiers alive in the filth of trench warfare. Try as he might, it was a losing battle. Even if he could sew the broken bodies back together, they would die from infection.

Just a slight cut would redden. Within days the infection would spread and the soldiers would die in misery, the medics standing by helplessly. Gerhard Domagk vowed that if he lived through the war that he would enter medical research and try to find a treatment for these infections.

He followed through on his vow and spent years in medical research. He was nearing his long sought goal when his daughter got a cut on her arm. He knew from deadly experience what would happen next. The infection would travel up her arm. If her arm was amputated she might survive.

He spent the night agonizing. The next morning he had made his decision. He filled a syringe with his experimental drug. He injected it into his  daughter. She lived. Dr. Gerhard Domagk had invented the first antibiotic. He won the Nobel prize in 1939.

daughter. She lived. Dr. Gerhard Domagk had invented the first antibiotic. He won the Nobel prize in 1939.

The new drug was a marvelous technical advance. It saved countless lives. But it could not be used orally. Now our story shifts back to America.

Harold Watkins, a chemist at Massengill Pharmaceuticals in Tennessee, developed an oral dosage form. It was a really good product. Not only was it a drinkable form of a powerful antibiotic but it also had raspberry flavoring dissolved in it; perfect for children.

It sold rapidly through the south. There was only one problem. The solvent that the chemist had used to dissolve all the components was poisonous.

Soon, disturbing reports began to surface of patients getting sick. Agents from FDA were dispatched to try to discover the cause of the illnesses. It took considerable time to back track to the suspected source.

When they eventually discovered that the drug had been produced by Massengill they ran into a roadblock. Massengill had kept no records of where the drugs had been shipped. They had no way to pull the drug off the shelves.

Furthermore, Massengill had done no toxicity testing of the new drug or its ingredients. No-one had any idea what about the drug was causing the deaths.

In the meantime parents were watching their children progress through abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, cramps, headaches, blindness, and seizures before finally falling into a coma and dying. It usually took a week or two for the children to die. The family had no idea why it was happening.

Dr. Archibald "Archie" Calhoun of Mt. Olive, Mississippi was one of the doctors who had prescribed Elixir Sulfanilamide to his patients. He began prescribing Massengill's liquid medication in mid-September, after receiving a sales call from a company rep.

One of the patients was his longtime friend, the Reverend James Byrd. When Calhoun received the company's October 19 telegram warning of the elixir's potential to kill, he "rode all night visiting every patient that I could remember prescribing to".

In a public letter, Dr. Calhoun expressed his anguish at the fatalities and his role in them:

“Nobody but Almighty God and I can know what I have been through these past few days. I have been familiar with death in the years since I received my M.D. from Tulane University School of Medicine with the rest of my class of 1911. Covington County has been my home. I have practiced here for years. Any doctor who has practiced more than a quarter of a century has seen his share of death.

"But to realize that six human beings, all of them my patients, one of them my best friend, are dead because they took medicine that I prescribed for them innocently, and to realize that that medicine which I had used for years in such cases suddenly had become a deadly poison in its newest and most modern form, as recommended by a great and reputable pharmaceutical firm in Tennessee: well, that realization has given me such days and nights of mental and spiritual agony as I did not believe a human being could undergo and survive. I have known hours when death for me would be a welcome relief from this agony." (Letter by Dr. A.S. Calhoun, October 22, 1937)

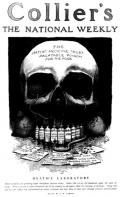

The newspapers picked up the story and made it front page headlines. Massengill had named their new drug Elixir Sulfanilamide. It was known in the newspapers as the Elixir of Death.

Samples of the drug were sent to Chicago where researcher Dr. Frances Kelsey worked frantically to analyze the drug. She found that the culprit was the solvent that Watkins used to solubilize the active ingredient, diethylene glycol, a component of anti freeze.

In the end 105 people died, a third of them children. FDA investigators seized Massengill's elixir and took them to court. The Agency was stymied, however, because Massengill had broken no law.

FDA was required by the law to prove intent on the part of the defendant. Clearly Massengill had not intended to kill their customers.

Dr. Samual Evans Massengill, the firm's owner, said: "My chemists and I deeply regret the fatal results, but there was no error in the manufacture of the product. We have been supplying a legitimate professional demand and not once could have foreseen the unlooked-for results. I do not feel that there was any responsibility on our part."

After much legal wrangling the court fined the company $26,000 for incorrect labeling.

But there were no winners in this conflict. Harold Watkins died of a self-inflicted wound while cleaning his handgun. To this day there are rumors that Harold Watkins' ghost walks the building that was once Massengill Pharmaceuticals.

Next time: Seal Limbs

Add new comment