The Heinrich Safety Pyramid and Quality

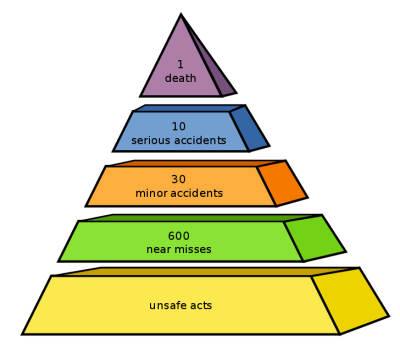

The Heinrich Safety Pyramid has been used in personnel safety management for near a century. Based on research done by Herbert Heinrich in the 1930s, it stated that the number of injuries in a workplace increases as the severity of the recorded injury goes down. In later versions by Frank Bird in the 1960s the ratios were modified to:

The Heinrich Safety Pyramid has been used in personnel safety management for near a century. Based on research done by Herbert Heinrich in the 1930s, it stated that the number of injuries in a workplace increases as the severity of the recorded injury goes down. In later versions by Frank Bird in the 1960s the ratios were modified to:

1 death:

10 serious accidents

30 minor accidents

600 near misses

Unsafe acts

Heinrich’s theory of proactive safety allowed companies to increase the rate of safety improvement by pushing safety investigations further down the severity scale.

Whereas previously companies had only investigated deaths and serious accidents [BTW we don’t call them accidents any more], now they could amplify their game and drive injuries down precipitously. The underlying theory can best be explained with an example.

Suppose someone incorrectly positions a 55 gallon drum on the top rack in a warehouse. Now, due to random vibrations from forklift traffic and trucks banging against loading docks, the drum falls to the floor. The theory says that for every 641 times that the drum falls

600 will only require that the floor be repaired and the mess be cleaned up.

30 will have landed on someone’s toe.

10 will have landed on someone’s foot.

1 will have landed on someone’s head, and there will be a big mess to clean up.

Underlying all of these outcomes is ONE unsafe act. A human being placed that drum in an unstable position. The brilliance of the theory is that one root cause investigation can save 41 injuries and a bunch of money.

When you have plenty of data coming in to the analyst, it becomes easy to pinpoint the trends and prioritize your corrective actions. With only a small data set of serious injuries and deaths, you are rolling the dice with your corrective actions. It is impossible to prioritize and you are literally on a death-watch…er, if you have a large data set of serious injuries and deaths, update your resume.

A critical part of the process is what you do with all the data you're collecting. If you don't organize it, you'll be overwhelmed with trivia. The answer, as with all large datasets, is to turn data into knowledge. This means tracking trends, prioritizing, and all else that good managers do.

Heinrich’s Pyramid has since been criticized by ankle-biters who whine that the numbers are not accurate. These minutiae have no impact on the overall theory nor, most importantly, what a company should do when it is serious about injury reduction.

A more thoughtful criticism came from W. Edwards Deming who said that blaming the injuries on human action was incorrect. The reality is that management controls what humans do in the workplace. Being a devoted disciple of Deming, I, of course, believe that allowing the root cause investigation to stop at an unsafe act by a worker would be completely destructive. The investigation has to dive deeper into the system that caused that worker to short-circuit the task. It has to ask why the management system caused the worker to incorrectly position the drum.

Nevertheless, despite the caveat from Demining, I believe that the Heinrich Pyramid can provide useful practices for improving quality.

I’ve seen workplaces where the safety culture encourages workers to point out to their peers when they are performing an unsafe act. These acts are recorded and followed up - without threat to the worker - to find the root cause and correct it. These places have insanely low injury rates in some highly hazardous industries. It took a lot of work [How can you shorten that process?] for them to instill a culture where the workers felt psychologically safe enough to help each other by calling attention to a peer’s unsafe act.

If this culture could be transplanted into Quality Management, it could dramatically reduce defect rates.

My question is do you think the Heinrich Pyramid can be used in Quality Management?

Comment below.

Add new comment